"Hang On To Your Hope"

An intimate look at the life and writing of E.B. White, one of America’s most inspiring and distinctive writers

Beloved American author E.B. White recently celebrated another birthday from the heavens. July 11th marked 125 years since the great wordsmith was born in Mount Vernon, New York. White is one of those writers whose influence has most likely been around since your youngest days. Many kids, both in the states and abroad, are introduced to his children’s books when they’re still infants. Both Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little are two of his most popular story-books. You likely have a copy of one or both of them on your bookshelf.

While his children’s books remain wildly popular, he was a dynamic writer whose articles and essays spanned many topics. Wading through his svelte, masterful literary style means you get to know White on a more personal level than you ever could by trying to strike up a conversation with him.

Let’s dive right into the wonderful works and life of the introverted and dedicated writer, Elwyn Brooks White.

A Romantic Naturalist

E.B. was an understated man who let his work do the talking. His family was the same. Family members displayed a passion for both skill and creativity with the career paths they chose. While White went the professional route with words, other family members were landscape architects, boat builders, inventors and musician-entrepreneurs. After graduating from Cornell University, he worked for United Press International, more commonly known as UPI, as a reporter.

In 1927 he officially came on board as a staff member of The New Yorker magazine, signifying the birth of what would become an enduring legacy. He wrote for the magazine for decades, producing essays, commentary, and articles. The scope of his work while at The New Yorker is documented in the collection, Writings from The New Yorker.

Even from his early days at the publication, his confident yet humble writing style made for a unique reading experience. He always strung words together with ease, creating a melodic experience with plenty of gentle punch.

In the introduction to the book, editor Rebecca M. Dale compares the author to one of America’s most treasured fellow, outdoorsy writers, Henry David Thoreau:

“Like Thoreau, White delighted in exploring the fullness of life as an individual. Like Thoreau, he was divided between “the desire to enjoy the world (and not be derailed by a mosquito wing) and the urge to set the world straight.””

The essence of his style could be framed as a Romantic Naturalist. He observed the world as it was, with keen vision and da-Vincian appreciation for even the smallest of Earth’s creations. In the foreword to an edition of White’s book, Charlotte’s Web, author Kate DiCamillo quotes him as confessing once upon a time, “All that I hope to say in books, all that I ever hope to say, is that I love the world."

White’s outlook on life, which naturally weaved itself into all of his writing, is poignantly captured in the opening entry to Writings from The New Yorker. The short-but-sweet entry titled, “Life,” shows what power an expert writer can wield in just one paragraph. The entry can be found in the book’s section titled, Nature:

“At eight of a hot morning, the cicada speaks his first piece. He says of the world: heat. At eleven of the same day, still singing, he has not changed his note but has enlarged his theme. He says of the morning: love. In the sultry middle of the afternoon, when the sadness of love and of heat has shaken him, his symphonic soul goes into the great movement and he says: death. But the thing isn’t over. After supper he weaves heat, love, death into a final stane, subtler and less brassy than the others. He has one last heroic monosyllable at his command. Life, he says, reminiscing. Life.”

The New Yorker Years

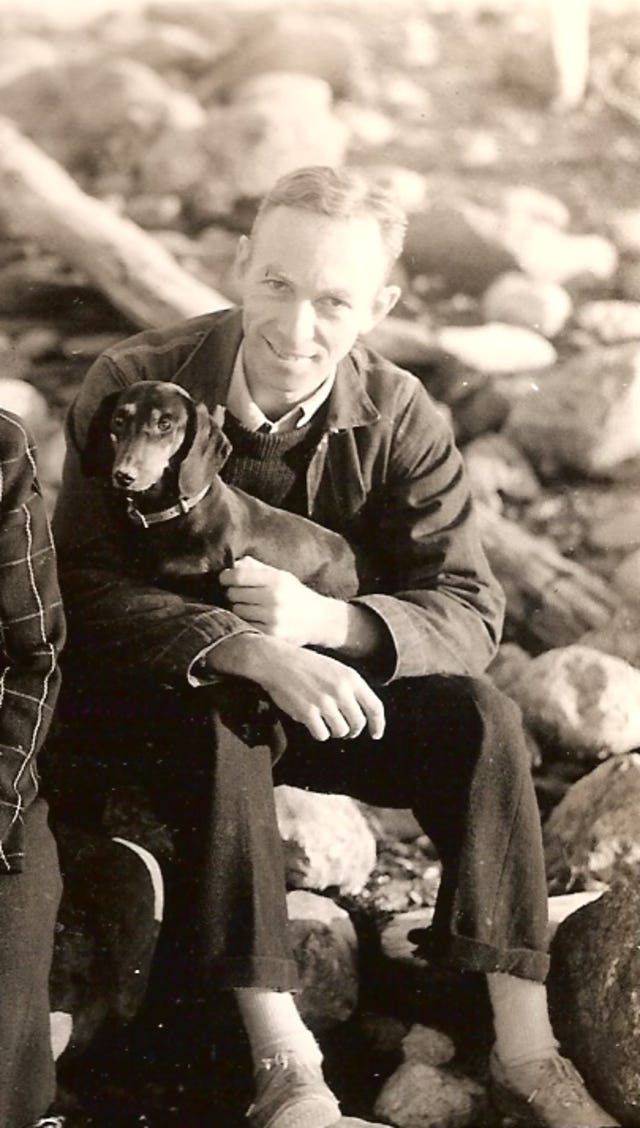

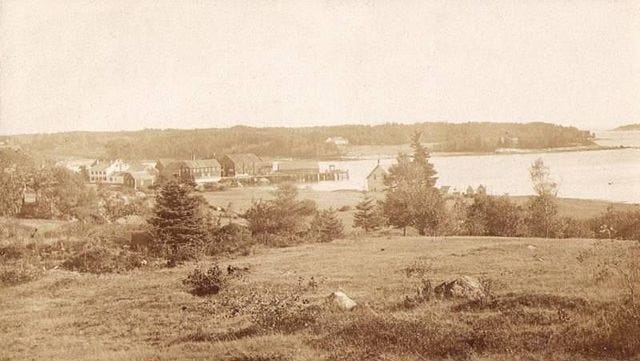

White loved the outdoors. Yes, he was often fixed at his typewriter. But he was never too far from a view of some body of water. He was an ardent sailor, loved animals, all types of weather, and though he spent much time in the hustle and bustle of New York streets, he preferred farm life to city life. His respite could be found in his quiet, seaside cottage in Maine.

In his later years, he was adamant that the cottage stay hidden in its little corner of heaven. Publications that have covered the legacy of the residence have also made sure to respect these wishes, stating, “...E.B. White simply wanted to be left alone, to write and to farm and to be a member of the community. He did not want his home to become a shrine, a museum, a writers’ retreat; he wanted it to stay just a family home.”

His granddaughter, Martha, feels a strong connection to the legacy of her grandfather, much like other members of White’s family. Martha echoes E.B.’s sentiment. News outlets have stated in regards to her and her grandfather’s wishes for his former property to remain under the radar, “She hopes it will forever be that way.”

In the beginning pages of another great American classic, William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, he spends time reflecting on White’s significant personal and professional influence:

“One of the pictures hanging in my office in mid-Manhattan is a photograph of the writer E.B. White. It was taken by Jill Krementz when White was 77 years old, at his home in North Brooklin, Maine. A white-haired man is sitting on a plain wooden bench at a plain wooden table—three boards nailed to four legs—in a small boathouse. The window is open to a view across the water. White is typing on a manual typewriter, and the only other objects are an ashtray and a nail keg. The keg, I don’t have to be told, is his wastebasket.

Many people from many corners of my life—writers and aspiring writers, students and former students—have seen that picture. They come to talk through a writing problem or to catch me up on their lives. But usually it doesn’t take more than a few minutes for their eye to be drawn to the old man sitting at the typewriter. What gets their attention is the simplicity of the process. White has everything he needs: a writing implement, a piece of paper, and a receptacle for all the sentences that didn’t come out the way he wanted them to.”

Even White’s coworkers at The New Yorker were surprised by how committed he remained to his introverted nature after he gained esteem. One of his colleagues, writer and illustrator James Thurber, once referred to White in his book Credos and Curios as a “quiet man” who preferred the office fire escape as an escape route from having to talking to people:

“Most of us, out of a politeness made up of faint curiosity and profound resignation, go out to meet the smiling stranger with a gesture of surrender and a fixed grin, but White has always taken to the fire escape. He has avoided the Man in the Reception Room as he has avoided the interviewer, the photographer, the microphone, the rostrum, the literary tea, and the Stork Club. His life is his own. He is the only writer of prominence I know of who could walk through the Algonquin lobby or between the tables at Jack and Charlie's and be recognized only by his friends.”

“The Sea and the Wind that Blows”

In White’s true self-deprecating style, he never fancied himself a sailor worth a salt, but he loved to sail his entire life nonetheless.

In one of his most moving essays, “The Sea and the Wind that Blows,” he documents his love of boating and the story takes on a double meaning. The reader soon realizes he’s not just talking about boats, he’s talking about life. So it goes with White’s plentiful literary contributions:

“When does a man quit the sea? How dizzy, how bumbling must he be? Does he quit while he's ahead, or wait till he makes some major mistake, like falling overboard or being flattened by an accidental jibe? This past winter I spent hours arguing the question with myself. Finally, deciding that I had come to the end of the road, I wrote a note to the boatyard, putting my boat up for sale. I said I was "coming off the water." But as I typed the sentence, I doubted that I meant a word of it.

If no buyer turns up, I know what will happen: I will instruct the yard to put her in again—"just till somebody comes along." And then there will be the old uneasiness, the old uncertainty, as the mild southeast breeze ruffles the cove, a gentle, steady, morning breeze, bringing the taint of the distant wet world, the smell that takes a man back to the very beginning of time, linking him to all that has gone before. There will lie the sloop, there will blow the wind, once more I will get under way. And as I reach across to the black can off the Point, dodging the trap buoys and toggles, the shags gathered on the ledge will note my passage. "There goes the old boy again," they will say. "One more rounding of his little Horn, one more conquest of his Roaring Forties." And with the tiller in my hand, I'll feel again the wind imparting life to a boat, will smell again the old menace, the one that imparts life to me: the cruel beauty of the salt world, the barnacle's tiny knives, the sharp spine of the urchin, the stinger of the sun jelly, the claw of the crab.”

E.B. White is an author whose works act as life-long companions. He’s a sage, a guide, and a best friend. His romantic view of life and naturalist appreciation of even the finest details of existence make his essays and books resources to return to again and again for inspiration.

When a struggling fan wrote to him about his concern with his own negative outlook on life and the human race, Mr. White offered him these sobering words to close out his response:

“Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day.”

What a wonderful tribute to an author who clearly means a lot to you. The only White books I've ever read are Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little. I've also made use of Elements of Style, although I've never read it cover to cover, but I am inspired to read more if I can.

I especially resonated with a passage about White you quote in your essay:

“Like Thoreau, White delighted in exploring the fullness of life as an individual. Like Thoreau, he was divided between “the desire to enjoy the world (and not be derailed by a mosquito wing) and the urge to set the world straight.””

You could almost say that that is my credo. Thanks for making me ponder it!

Same birthday as my mom z"l ❤️ 💔 - this July 11 she would have been 100

z"l - is a contraction of Hebrew letters for: may her memory be a blessing

Great article Rebecca. Always nice to read your erudite posts