Poetry For The Happy Warrior

The life of great Romanticist poet William Wordsworth and the dawning of a new literary age

Before we get into today’s article about the great William Wordsworth, a bit of Classically Cultured news. Read-alouds of my articles will now be available to CC subscribers. So if you prefer to listen rather than read, I’ve got you covered! Simply click below to access this as a podcast episode and enjoy. Let me know if you like this new feature in the comments. I’m hoping to build out the Classically Cultured podcast with a ton of extra, exciting content moving forward (these podcast episodes are also available on Spotify!). But for now, I’m getting it started with these article read-alouds as I build out my podcast equipment setup. If you prefer to read rather than listen, just scroll past the podcast episode link to dive into the article. Cheers and happy reading (or listening)!

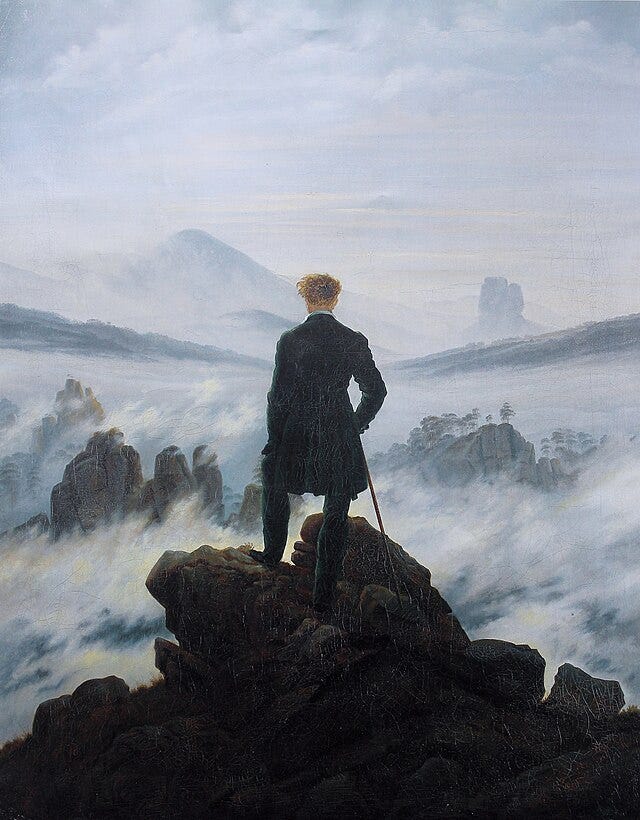

April is National Poetry Month in America and we are well underway. When I realized the month-long celebration had arrived, I quickly began making a list of possible topics to cover here at Classically Cultured. One of my main objectives is to help reignite a love of good poetry. I’ve covered poet William E. Henley’s inspirational life story and his brilliant poem “Invictus.” I’ve also released a bit of my own poetry. After much deliberation for National Poetry Month though, I decided to kick this series of poetry-focused posts off with a profile of one of my favorites, Romantic poet William Wordsworth. He was a man who loved nature. He loved thinking. He loved life. And his love for all these things sprung from the pages of his work.

I hope you enjoy my latest article, and if you enjoy the content here at Classically Cultured, I’d love for you to join our humble, growing community of book worms, thinkers, philosophers, and art-lovers. You can subscribe via the Subscribe button included at the bottom of this article. Cheers!

Lyrical Ballads

Wordsworth is one of those poets whose words read like music. Like the flowing movements of birds, trees, and landscapes that inspired him, his words are brimming with melody and life. One of his most notable works, Lyrical Ballads, which he authored alongside his friend and fellow poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, kicked off one of poetry’s greatest movements in history, The Romantic Age.

At the root of all of Wordsworth’s work, Lyrical Ballads and otherwise, is the all-important subject of life. His life-affirming poems are inspirational, invigorating, comforting, and thought-provoking. This is a man, who despite heartbreak and times of elation, never forgot to experience living to its fullest extent. And to him, that meant spending time in nature, creating great works of art, contemplating the nature of man and what freedom means, and charting his own path.

Romantic poets are some of my favorites for reasons I just listed pertaining to Wordsworth. Their passion is infectious. And passion is one of an artist’s most important tools.

Getting Romanticism Right

Romanticism is one of western civilization’s most successful artistic movements. But its lack of a proper definition caused its own demise. Some of its defining elements are correct, like the movement’s embrace of individualism. But other parts of the definition suggest Romanticist poetry is more surreal than real. And that it’s floating in the ether of the cosmos, rather than down here on earth where all the Romantic poets were doing their work.

Words like emotion, imagination, and sentimentality are thrown around by Google’s top results on the subject. To me, even when learning about Romanticism in high school before diving into the philosophy of the Transcendentalists, this definition didn’t fit the Romantic poetry I was reading.

Yes, poetry of the Romantic age is full of passion. But it's not reckless passion powered by unchecked emotion and fantasy. It’s a purposive passion. One that suggests we should listen up, because these guys really know what they’re talking about.

I discovered I wasn’t alone in my assessment while reading Ayn Rand’s book of essays, The Romantic Manifesto. In her chapter, “What Is Romanticism?”, she becomes the first to give a thorough and proper philosophical treatment of the poetic school of thought.

“Such were the roots of one of the grimmest ironies in cultural history: the early attempts to define the nature of Romanticism declared it to be an esthetic school based on the primacy of emotions — as against the champions of the primacy of reason, which were the Classicists (and, later, the Naturalists). In various forms, this definition has persisted to our day. It is an example of the intellectually disastrous consequences of definitions by non-essentials — and an example of the penalty one pays for a non-philosophical approach to cultural phenomena.”

For Rand, Romanticists wrote poetry with a philosophical primacy of values. And I have to agree. She expands on the point:

“What the Romanticists brought to art was the primacy of values… Values (and value-judgments) are the source of emotions; a great deal of emotional intensity was projected in the work of the Romanticists and in the reactions of their audiences, as well as a great deal of color, imagination, originality, excitement and all the other consequences of a value-oriented view of life. This emotional element was the most easily perceivable characteristic of the new movement and it was taken as its defining characteristic, without deeper inquiry.”

An accurate understanding of Wordsworth’s Romanticism allows readers to identify all the values, emotions, and passions of his work under proper context. And Wordsworth valued a lot. And quite often, it was at odds with what was en vogue with the times.

Into The Light of Things

Born in 1770 in England to parents John and Ann Wordsworth, William grew up on a property that belonged to his father’s employer. His childhood home was in a rural area, and he was surrounded by miles of nature and water. The natural world would become his earliest and one of his most defining influences. Because of his love of the natural world, he developed a love of its “beauteous forms.” This colored the language of his poetry.

One of my favorite poems of his, “The Tables Turned,” speaks of nature's importance. And not just the setting that surrounds us, but the importance of nature from a philosophical standpoint. Here’s one of my favorite lines from the poem. Notice how “nature” is capitalized:

“Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.”

The poem has a light-hearted but passionate tone, and beckons readers to “quit” their books and get out in the world and experience all it has to offer.

“Up! up! my Friend, and quit your books;

Or surely you'll grow double:

Up! up! my Friend, and clear your looks;

Why all this toil and trouble?The sun above the mountain's head,

A freshening lustre mellow

Through all the long green fields has spread,

His first sweet evening yellow.”

His poem “Most Sweet It Is” also reflects on the importance of spending time in nature. And it offers telling clues about Wordsworth’s own value-judgements — what he holds dear. These value-judgements give his view of man a certain hue, one that is brightly colored with controlled intensity:

“Most sweet it is with unuplifted eyes

To pace the ground, if path be there or none,

While a fair region round the traveller lies

Which he forbears again to look upon…”

The poem continues, and we get a glimpse into what is desperately important to the poet:

“If Thought and Love desert us, from that day

Let us break off all commerce with the Muse…”

The Rise of a Poet

Despite the picturesque backdrop that colored Wordsworth’s earliest years, his upbringing among an unbridled rural oasis didn’t last long. He lost both of his parents while still a boy, and was subsequently separated from his sister, Dorothy, who he was very close with. As his family life disintegrated, he relied on his education and creative projects to cope with the significant loss.

He was no stranger to political upheaval either. During his time, he saw the events and aftermath of the French Revolution. He also took note of the birth of America and all her glory and freedom. Because of the rapidly changing political landscape both at home and abroad, his own political leanings changed throughout his life. He was at one point a Democrat who considered his voice one of the “common man.” But later in life he embraced the Republicanism of the New World that had created the freest country on earth. Due to despotism he was all too familiar with in late 1700s England, he understood the importance of a system of checks and balances, and a government kept at bay by a self-reliant population not too keen on authority figures meddling in their daily affairs.

At the heart of Wordsworth’s philosophical and political convictions though was always the belief that man should be a free, autonomous being.

In 1795, now a grown man, William was finally reunited with his sister Dorothy after many years apart. They settled into a house together and Dorothy’s presence acted as a stabilizing force that ushered in Wordsworth’s most successful artistic period.

Even after all the years apart, William wrote that his sister helped him find his “true self” again, and “preserved me still/ A poet.” With order returned to his life, William experienced an artistic renaissance.

The Great Decade

Critics agree the English poet produced his best works during what they call “The Great Decade.” He not only produced a large amount of poetry and writing, according to reviewers, his most “mature” work was written during this fertile time frame from around 1797 to 1807.

In 1798, Wordsworth co-authored Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poetry, with his friend and fellow poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The collection drew the ire of quite a few critics. It also kickstarted the Romantic Age of poetry and literature.

Wordsworth loved nature, solitude, and contemplation. He believed these things were paramount to man’s nature, and without them men could not lead a proper existence. As the world was becoming more industrialized, his beliefs stood in contrast to booming urban areas, a rising population, and an increasing lack of undisturbed, bountiful landscapes.

He received so much criticism he used the preface of subsequent editions of Lyrical Ballads to refute his critics.

Despite the controversy he faced, he also had plenty of supporters.

While he and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads kicked off the Romantic movement, Wordsworth’s Prelude became one of the movement’s greatest works. And many supporters and critics alike agreed, the autobiographical epic poem also titled “Growth of a Poet’s Mind,” was his greatest individual achievement.

A Happy Warrior

While consensus regards Prelude as his greatest work, I think one of his poems, “Character of the Happy Warrior,” represents the essence of Wordsworth’s skill as an artist, and human being.

Wordsworth’s poetry can teach us a lot, but the man behind the poems can teach us a lot too. Through all of the loss (he not only lost his parents, but two of his own children while they were still in infancy), heartache, war, and criticism William remained steadfast in his convictions. He also remained dedicated to his work, which he viewed as his refuge from tragedy and adversity.

His days spent in wonderment of the beauty of nature always refueled him. It helped him walk through more than woods and meadows. It helped him walk through all of life’s fires, and lead the life of 10 men even though it was just one.

William’s story and poetry can help us all get through those hard days and rediscover the beauty that is often just outside our back door. Here’s an excerpt from his poem, “Character of the Happy Warrior.” You can read the entire poem here. I hope his words serve as a healing force to life’s challenges. I hope they help you whenever you may need it:

“Who is the happy Warrior? Who is he

That every man in arms should wish to be?

—It is the generous Spirit, who, when brought

Among the tasks of real life, hath wrought

Upon the plan that pleased his boyish thought:

Whose high endeavours are an inward light

That makes the path before him always bright;

Who, with a natural instinct to discern

What knowledge can perform, is diligent to learn;

Abides by this resolve, and stops not there,

But makes his moral being his prime care…More skilful in self-knowledge, even more pure,

As tempted more; more able to endure,

As more exposed to suffering and distress;

Thence, also, more alive to tenderness.

—'Tis he whose law is reason; who depends

Upon that law as on the best of friends…Finds comfort in himself and in his cause;

And, while the mortal mist is gathering, draws

His breath in confidence of Heaven's applause:

This is the happy Warrior; this is he

That every man in arms should wish to be.”

Oh, how I love this "Character of the Happy Warrior" poem! Thank you for introducing this to me. :o)