Mary Oliver: More Than a “Nature Poet”

Newly released archives at the Library of Congress offer a bird’s-eye view of the introverted, modern poet, and showcase the breadth of her intellect

There is so much to learn from the poet, Mary Oliver. In the summer of 2024, thanks to executors of her estate and the Library of Congress, around 40,000 items from The Mary Oliver Papers were made available to researchers in the LOC’s Manuscript Division. From what I can tell, much of the contents have to be requested in order to view. But the organization has given us a healthy glimpse into what researchers will find, including letters, manuscripts, photographs, and journal entries.

A Form of Prayer

One of my favorite pieces is an excerpt from one of her many journals she always had on hand. The pages document various bird sightings during her long walks in the woods. In the year 1991, on one page (or maybe two pages) she documented forty different species of birds seen on her excursions.

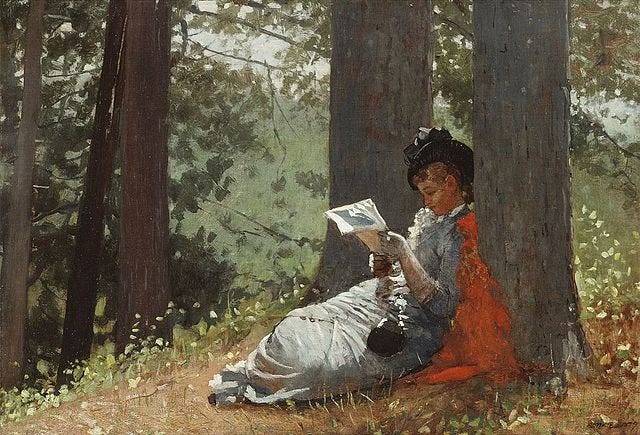

Oliver was a noble woodswoman. Much like her key influences, which include transcendentalist pioneer Ralph Waldo Emerson, Romantic poet William Wordsworth, and poet-visionary Walt Whitman, she valued the natural world as a way to orient herself with reality and ruminate on the meaning of existence. She gently and patiently pulled every ounce of inspiration she could out of the petite milk thistle and the mighty oak tree.

Her love of nature contained an air of divinity, and it is present throughout most of her work, whether poetry or prose.

While covering The Mary Oliver Papers debut, the LOC stated that Oliver, “...posited that every tree, every bush, and every flower is a reason to expound, and that the gladness she felt in response to the natural world is its own form of prayer.”

Her New York Times best-selling collection of essays titled Upstream contains this theme throughout each entry. I often turn to Oliver in times of mental burnout. When my mind won’t stop racing, I reach for her poetry, which reminds me to slow down, focus on the song of the red bird and the flight of the distant, hungry hawk. Within the pages of her introductory essay, she gives me answers to what gnaws at my mind. How do I quiet my racing collage of random thoughts to focus on the important task at hand?

Her eternal words advise me to remember: “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

Don’t just look, see. Don’t just walk, be present. Don’t just exist, live.

With these thoughts, I’m reminded of one of the greatest literary quotes she ever graced us with:

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

“Saved by the Beauty of the World”

While she’s well-known as a sort of secular priestess of the natural world, documents within The Mary Oliver Papers clearly show she tackled a variety of subjects while creating.

A letter included in the collection details the poet’s reluctance to being pigeon-holed as a “nature poet” while applying for a Guggenheim Fellowship. In the letter, she states:

“I’m interested in America as a natural force upon our lives. I am not a nature writer, or a conservationist, or an escapist—rather I see the influence of our very singular country upon American life in all facets of that life, spiritual and actual, and whether we know it or not. I see a creative statement about these forces as a possible enrichment of that influence.”

Regarding the spreading of her creative wings, the LOC said, “...she was interested in many things, including democracy in the United States and the regional variety of its people. When awarded the fellowship, she used it to work on her poetry collection, American Primitive, for which she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1984.”

While Emerson is described as an American philosopher, Oliver is described as an American poet. And Oliver’s words on the country she lived in show “American” isn’t simply a descriptor for location, it’s a descriptor for a one-of-a-kind philosophy. American poets and philosophers aren’t simply located in the U.S. American poets and philosophers offer a unique blend of optimism and hope, self-reliance and boot-strapping capability, an individualist perspective, and a stubborn ability to not be boxed into physical identity. They have earned the right to not be taken at face value, but mind value.

Oliver kept an individualist perspective even in nature. Like people, she viewed trees, plants, and flowers as having their own unique markers. In her essay “Upstream,” she lets us in on one of her rituals:

“One tree is like another tree, but not too much. One tulip is like the next tulip, but not altogether. More or less like people—a general outline, then the stunning individual strokes. Hello Tom, hello Andy. Hello Archibald Violet, and Clarissa Bluebell. Hello Lilian Willow, and Noah, the oak tree I have hugged and kissed every first day of spring for the last thirty years. What a life is ours! Doesn’t anybody in the world anymore want to get up in the middle of the night and sing?”

With a poet as serene and joyful as Oliver, one might think her childhood days spent in the woods was indicative of a happy youthful experience. However, the more we learn about the private poet, the more we realize she took to the woods to escape her home-life. Her time spent outdoors represented freedom, peace, and mental stimulation she craved so much but didn’t get at home. While chatting with journalist and author Krista Tippett in an interview with On Being, Oliver offered us a rare, enlightening glimpse into her earliest days:

Tippett: And then you talk about growing up in a sad, depressed place, a difficult place. You don’t belabor this, I mean, and in other places — there’s a place you talk about you were one of many thousands who’ve had insufficient childhoods, but that you spent a lot of your time walking around the woods in Ohio.

Oliver: Yes, I did, and I think it saved my life. To this day, I don’t care for the enclosure of buildings. It was a very bad childhood — for everybody, every member of the household, not just myself, I think — and I escaped it, barely, with years of trouble. But I did find the entire world, in looking for something. But I got saved by poetry, and I got saved by the beauty of the world.

Courage—The Mother of all Virtues

While some might view Oliver a bit like another transcendentalist thinker, Henry David Thoreau—introverted, primitive, and above some supposed selfish need to leave behind a legacy—one clue involving her weathered typewriter offers a much bolder take on the reserved wordsmith.

While Oliver worked on her many projects, a piece of paper stayed taped to her typewriter at all times.

In big, bold letters strapped right in the middle of her machine, “COURAGE,” printed in all caps, could be seen whenever she was striking away at the keys.

Not long ago, ivory tower intellectual types launched an attack of sorts on Oliver, questioning whether she was actually a poet worth remembering.

At Sermons in Stones, one writer states, “I am not a person who believes that poems should have morals tacked on to the end. In my experience, the best poems, the ones that eventually turn my life inside out and…inform me that I must change it, are rarely the ones that tell me in plain language what I ought to do. Oliver’s poems are, in a word, obvious.”

Writer Henry Oliver at

offers a rebuttal:“The problem, for detractors, is that Mary Oliver is not analytic or detached or cynical or knowing. She is not using literature for some bigger, ideological purpose. Instead, heaven forbid, she is earnest. “How rich it is to love the world.” Yes! Yes! How rich indeed! Of course, you often aren’t permitted to talk like that in many modern literary groupings. Eh, their loss. Her work is a standing rebuke to their disinterest. “The world offers itself to your imagination.””

Indeed, one of the big reasons as to why she’s not all that impressive to ivory tower intellectuals is the fact that the everyday reader can gain something from her poetry. To the ivory tower types, this makes her “average.” To us revolutionary intellectuals, the ones who aren’t afraid of having more questions than answers, this is precisely why she’s such a remarkable and worthy poet.

Announce Your Place “in the family of things”

One of my favorite poems of hers, which instills much practical wisdom, is her work, “Wild Geese.”

Here’s Oliver reading it for an audience:

With one listen to that poem, which strikes me as a devotional that could rival a psalm, I challenge anyone to tell me with any seriousness how in the world she’s not one of the best poets to ever walk this good, green earth.

Her words comfort me just like the words of another great American writer, John Steinbeck, in his novel East of Eden:

“And now that you don’t have to be perfect, you can be good.”

Is his practical style also “middlebrow,” as she’s been described? I don’t think so.

The broken-hearted turn to poetry. The idealists trying to make sense of a highly unideal world turn to poetry. The battle-scarred realists looking for a salve, for a bit of wonderment, turn to poetry.

When I turn to poetry, don’t give me a fortune cookie with an ethereal prize inside that turns into a guessing game as I try to figure out what it means—give me a well thought-out recipe I can whip up in my own kitchen, helping me shape my own destiny.

Don’t give me the dance of a fable, give me the knock of clarity.

Give me Mary Oliver.

Want to dive deeper into Oliver’s works? Find her best-selling collection of essays here, and a selected collection of her poems, titled Devotion, here.

Are you a fan of Mary Oliver? What are some of your favorite works of hers? Do you feel she’s overrated? Let me know in the comments below!

I really enjoyed this! 🙏🏻

I have read several poems by Mary Oliver and am shocked that some people would call her “not a poet.” I want to read her essays, too - especially after I found this post. Excellent work!